As part of the Memory Week organized every two years by theB2V Memory Observatory, we invite you to explore the links between memory and trauma. How does it work? What are the links with PTSD, with genes? What is amnesia? How can we collectively remember an event?

Memory and trauma

How does memory work?

To remember or not to remember a past event, a face, an emotion felt at the movies... Behind it all lies a function that everyone uses without necessarily knowing it well: memory. Do you have no idea how memory works, or have you forgotten everything you thought you knew about it? Don't panic, we'll go over the basics together.

It's quite possible to remember a multiplication table you learned at school decades ago, but not at all the beginning of this article you've just read... In fact, there isn't just one memory, but many. They are generally divided into three main types.

Read more

At the very beginning of our journey is sensory memory. This is the first stage of memory. It involves the temporary reception of sensory information from our senses, such as sight, hearing, touch, taste and smell. This information is stored very briefly, usually less than a second, and acts as a kind of sensory buffer.

Next comes short-term memory; also known as working memory, this stage involves selecting, organizing and actively processing sensory information. The capacity of short-term memory is limited. Information that is not repeated or processed significantly is quickly forgotten.

Finally, there is long-term memory: this stage involves the long-term storage of important information. Long-term memory can store an almost unlimited amount of information for long periods. It is divided into several sub-categories, including episodic memory (memories of specific events), semantic memory (general knowledge) and procedural memory (skills).

Okay, but how does it work?

In addition to the different types of memory, there are also a number of processes associated with memory, which enable it to "function".

- Encoding

The process of encoding involves transforming sensory or short-term information into a form that can be stored in long-term memory. Encoding can be achieved in a number of ways, including repetition, association with existing information or memorization techniques. - Storage

This is how we "store" information within our memory, how we put it away in one place or another. This process takes more or less time, depending on the encoding that precedes it. - Retrieval

This is the process by which we recall and retrieve information from long-term memory when we need it. Retrieval can be influenced by a variety of factors, such as cues, emotional state, consistency of initial encoding and so on.

What does this have to do with post-traumatic stress disorder?

You can't really talk about post-traumatic stress disorder without talking about memory impairment... The two are intrinsically linked! One of the main symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder is memory impairment. "This is what we call the ' reliving syndrome '," explains Francis Eustache, neurologist and Chairman of the Scientific Advisory Board of the B2V Memory Observatory, in a video posted on their website. "These are intrusions, images in the broadest sense of the term, they can also be sounds, they can be smells, which are triggered by clues, i.e. elements that resemble the scene of the trauma," continues the scientist. In short, a memory that has become uncontrollable and memories that resurface in intrusive, frightening or even paralyzing ways.

False memories: panic in psychology

It's the trademark of many "gurus" and other false therapists: inducing false memories in their victims so as to cut them off from their loved ones, the better to take advantage of them. In the jargon of the fight against sectarian aberrations, this is known as the phenomenon of "induced false memories". This is nothing new; ever since induced false memories gave the USA a fright in the '80s, this dangerous practice has been a regular feature of the news. At the risk of discrediting the victims of dissociative amnesia, who are said to question the veracity of their recovered memories.

Read more

It's a chilling memory of an incestuous father who rapes his daughter Sophie when she's just a child. It's a memory that recounts the absolute forbidden, the one condemned by the courts with a heavy sentence. But on that afternoon in April 2012, it's not Sophie's father who appears before the judge. Because in reality, the memory is completely false. That day, Benoît Yang Ting, the forty-something's therapist, was accused of inducing false memories in Sophie, during a long and very expensive therapy - 238,000 euros, twelve years of sessions. "For three to five weeks, we'd arrive at his house at around 7:30 a.m., lie naked on the couch and remain motionless for six to eight hours," Sophie Poirot explained in court, according to Le Monde. "After a while, you can't tell what you've really been through". Next to her, another victim accuses Benoît Yang Ting of inducing false memories, in this case memories of parental abuse during childhood. Bernard, 58 at the time of the trial, is a management consultant. He had been visiting Benoît Yang Ting for 22 years, before realizing the hold he was under: "I was convinced that they [his parents] had wanted to kill me," he explained on the stand. "He kept saying that I wasn't really in pain, and that I had to go back in time to find the source of my suffering. Until the day when his 7-year-old daughter, whom he had taken to see the therapist, came out of the session claiming to have been abused by the nanny. In 2015, the therapist received a one-year suspended prison sentence on appeal for breach of trust.

The trial of Benoît Yang Ting was the first in France to address the issue of false memories. But this is not a new concept. Already described by Freud in 1896, it became particularly widespread in the USA in the 80s and 90s. At that time, many victims reported that their memories had suddenly returned, often in the course of therapy, and that they remembered old traumas - particularly childhood abuse. But all this has been shown to be false. The culprit: guru-like pseudo-therapists who saw this as a way of isolating their victims from their circle of friends and family, so as to better extend their hold. In the USA, this period of collective psychosis became known as the "Satanic Panic". A period during which many Americans were prosecuted for terrible crimes on the basis of testimony that turned out to have been induced by investigators. This led to a wave of lawsuits and controversy over the validity of memories recovered in therapy.

In 1992, the False Memory Syndrome Foundation was set up in the United States, bringing together families suddenly accused of incest by their child. In France, the PsyfmFrance association is leading the fight. In 2008, the France 2 program " Les Infiltrés " took an interest in the issue, filming a therapist accused of inducing false memories of incest in her patients. A few minutes into the first session, during which the undercover journalist claims to be consulting her to understand her lack of desire, the pseudo-therapist tells the young woman that this is a sign of childhood abuse, so violent that she has completely forgotten about it.

The first studies

Elizabeth Loftus, an American psychologist, was one of the first to explore the creation of false memories in the 1990s. The idea for this research came to her during a car journey in 1991. At the time, Elizabeth Loftus was already renowned for her work on how memory can be influenced. To demonstrate the possibility of creating a fabricated memory from scratch in an experimental situation, she set out to develop a vivid but non-traumatic memory, such as getting lost in a shopping mall as a child. After proposing this concept to her students, one of them successfully implanted this false memory in his 14-year-old brother. The young boy even produced very precise visual details of the false event.

Encouraged by these results, Elizabeth Loftus carried out a further study, recruiting adult volunteers to create false childhood memories. The results showed that some participants were able to form memories of wandering into a shopping mall at the age of 5, which was interpreted as evidence of the existence of false memories. At the time, Elizabeth Loftus' work divided the psychology community, between those who supported recovered memories in therapy and those who were concerned about false memories. These "memory wars" led to the questioning of memory retrieval therapies and the conviction of practitioners for manipulating their patients. Even today, some trauma specialists continue to criticize his positions, arguing that suggesting that false memories can be easily induced can call into question the credibility of testimonies from people who have undergone traumatic experiences.

Not to be confused with dissociative amnesia

This is the main warning from Pr Wissam El Hage, psychiatrist in charge of the Centre Régional du Psychotraumatisme Centre-Val de Loire. "It's sometimes a way of positioning oneself by questioning the veracity of certain memories. But dissociative amnesia has nothing to do with false memories," warns the psychiatrist. "A dissociated memory is one that has been recorded at a given moment, but which is difficult to recover in its entirety. A false memory is one that has no source memory."

In his view, it's impossible to confuse a so-called dissociated memory- i.e., a memory that can be recalled years after a traumatic event, for example - with a false memory that has been deliberately implanted in another person's mind. The dissociated memory would be more precise, with a beginning, an end and content, while the false memory would be more like a general impression. The false memory is "purely visual or narrative in nature", explains Wissam El Hage. "Whereas in traumatic memory or dissociated amnesia, we also have an emotional, sensory and motor component in addition to the other components."

The fact remains that too much talk about false memories, which, as we've seen, develop in very specific contexts, runs the risk of calling into question the word of the victims. The pseudo theory of parental alienation syndrome (a scientifically unfounded theory designed to undermine the voice of the child and the other parent, usually the mother) has been used, for example, to deny accusations of violence or abuse made by children.

Memory in the genes

What if we could "inherit" an ancestor's trauma, just as we inherit the color of their eyes or any other physical characteristic? This is what scientists are exploring through the notions of "intergenerational trauma" or transgenerational trauma. Traces of the traumatic event experienced by a grandparent or great-grandparent could thus be found... in our genes.

Read more

As a child, Ondine was often awakened by a terrible image: that of a man's head at the end of a pike, presented to the crowd. She has had this nightmare dozens of times. "All children have nightmares, but I've had them for a long time, always involving scenes of intense violence," she recounts. Today, Ondine Khayat is a writer. And from these nightmares, which she inherited from her grandmother, she has written a novel about transgenerational trauma, Le parfum de l'exil . She realized much later, however, that the scene of horror she had been dreaming about, and about which no one in her family had ever spoken, represented the figure of her great-grandfather, who died during the Armenian genocide.

"You realize just how much you're part of a human chain, in a very concrete and mysterious way," explains the author, who is no novice at this, her ninth novel. "This one was directly inspired by the story of my paternal grandmother, born in Marache, in the Ottoman Empire. She lived through the Armenian genocide, about which little is said, but also all the consequences of exile." Her father, Ondine Khayat's great-grandfather, was a prominent man. He was murdered, and the scene the writer dreamed of actually happened.

"In every family, there are heavy secrets, invisible loyalties, burdens that are passed down from generation to generation. We come from a people who have suffered a great deal. Every people has its own tragedies and hopes. We form a single human chain, each of us tirelessly called upon to understand, to learn, to repair." - excerpt from Le parfum de l'exil

"The strange thing was thatI hadn't been given any details - in general, people who experience this kind of trauma find it hard to talk about it. I retraced my family's steps in an absolute way, cross-checking other testimonies, and that's how I came to understand the origin of my suffering", says Ondine Khayat. Writing the novel enabled her to "soothe" this suffering and these symptoms akin to those of post-traumatic stress disorder. "Something was released and completed with the writing of the book," continues the author.

A question of epigenetics

Can trauma be passed on from generation to generation? According to an Ifop poll carried out in 2019 for the Observatoire B2V des Mémoires, more than one in two French people believe that it's possible to have post-traumatic stress disorder without having personally experienced trauma. In reality, there is no "transmission of trauma" in the sense that the parents' trauma would cause post-traumatic stress disorder in the children, but has psychological effects on the offspring. To explain this in part, researchers are working on what is known as epigenetics, the way genes express themselves according to the environment. This is where the mystery of this inheritance lies: when we experience intense stress, such as a traumatic event, our genome changes.

Read more

Epigene... what?

Epigenetics refers to the way in which genes are expressed. We have a certain genetic heritage, but our cells will call on certain genes and not others, depending on their place and function in our body. The expression, or lack of expression, of these genes can be modified, for example by the environment. Epigenetics focuses on these modifications. These changes are reversible. The DNA is not modified, but the genes are expressed or "muted" differently.

"These environmentally-induced changes in genetic functioning could be transmitted over several generations," explains Ariane Giacobino, a physician and specialist in epigenetics, in a book published in 2018 . "We are probably born with certain marks initially deposited on our ancestors' genes. Although we don't yet know the process, we do now know that these marks are reversible", continues the scientist.

Intergenerational or transgenerational?

In general, we speak of intergenerational transmission when it concerns two generations, that of the parents who experienced the trauma and that of their children who feel its effects. Transgenerational trauma is also used to refer to traumas that are older in the generations (for example, people today who are descendants of victims of the Holocaust or the Armenian genocide).

In 2015, researchers found evidence of transgenerational transmission of Holocaust trauma, through symptoms of post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety. "This is the first demonstration of the relationship between parental trauma and obvious epigenetic alterations, both in parents but also in their children, and shows insight into the severity of psychophysiological trauma on intergenerational effects," the study authors concluded.

History: necessary oblivion or duty to remember?

If post-traumatic stress disorder goes hand in hand with intrusive memories and an inability to forget, how are we to deal with the duty to remember the great events that made history - and potentially traumatize thousands of people? Faced with reminders of their traumas, don't people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder run the risk of reactivating their trauma at every commemoration? A brief history of the duty to remember and its link with the victims of history.

Read more

Every year, as the date of November 13 approaches, commemorations remind the world of the horror that occurred in Paris on that same day in 2015. TV programs adapt, some ceremonies are organized in the presence of elected officials and unknown citizens, the written press also takes up the subject and asks the question: what memory do we keep, collectively and individually, of these attacks? These commemorations, which remind us that we must not forget and which, on the contrary, link us to a duty to remember, do not come naturally.

To the question "Which terrorist attacks have had the greatest impact on you since 2000?", posed by the Credoc survey of the 13-November Program, the answers vary according to year and seasonality. "The attacks of January 2015 (Charlie-Hebdo, Hypercacher, police officers) follow a sinusoidal evolution that says a lot about the impact and responsibility of memorial policies through commemorations and media mobilization," explains Denis Pechanski, historian and director of research at the CNRS, in Mémoire au traumatisme. "It's as if, every January, this form of reminder highlights these attacks before fading away for the rest of the year, as the polls carried out in May and June indicate."

A recent expression

Duty to remember is a relatively recent concept in history, developed in the 1990s in connection with the Second World War and the Shoah in particular. "Le devoir de mémoire is the French title given in 1995 to a posthumous work by Primo Levi, based on an interview he gave in 1983 to two Italian historians", explains Olivier Lalieu, historian at the Shoah Memorial, in L'invention du "devoir de mémoire". "This publication, like the rediscovery of the author's work, popularized the expression, in the context of the 50th anniversary of the liberation of the camps. But this formulaic title is not by Primo Levi. It was chosen by the publisher because it is in keeping with the times, hijacking the very content of an interview in which Primo Levi shares his questions about the posterity of Auschwitz."

Contradicting the tradition of amnesty, by which States historically imposed oblivion during peace treaties, the expression "duty to remember" was quickly criticized by certain historians, who warned against this moral imperative taking precedence over the work of historical and scientific research. However, it has made it possible to emphasize and highlight the figure of victims, and to recognize their status.

Commemorations and trauma reactivation

What remains to be found is the place of victims in this duty of remembrance and its expressions. In a review of articles published in 2020, the authors looked at how victims experience and react to commemorations. "Twenty-six empirical studies examined the experience of post-traumatic stress and grief after commemoration," summarize the authors. "Commemoration can elevate stress levels and grief reactions, but it is also experienced as helpful by many people."

Should they be seen as a cathartic experience and a step towards resilience? As opposed to reactivating the trauma, collective commemorations could foster a sense of belonging among the victims who take part, and constitute a form of social support - the essential movement. "It's a moment of communion and solidarity that's very important to us. We commemorate the dead, but we also think of the living, and that's why we like to get together," Arthur Dénouveaux, president of the victims' association Life for Paris, told France Info in 2020.

32 GB of resilience

If individual memory functions through the three major processes of encoding, storage and retrieval, how does this organization adapt to digital memory? Will our ability to store information on clouds and good old USB sticks transform our memorization? We discussed all this with Jean-Gabriel Ganascia, professor of computer science at the Sorbonne.

Click HERE to read the interview.

"I've done nothing wrong".

"Today I feel more aware, more powerful too. I still feel the trauma, but I feel I have more control."

In 2022, Les rencontres de la photographie d'Arles honored the work of German photographer Mika Sperling with the exhibition "I have done nothing wrong". The artist worked on the issue of dissociative amnesia, in connection with her own history and the abuse she suffered as a child. She agreed to grant us an interview and present her work. Here are some of her works, a mixture of photographs and cut-outs.

"I started working on the project in 2019. My trauma was reactivated after the birth of my daughter; I felt extremely bad when I saw her in contact with older men. It made me very uncomfortable. I began to wonder why I felt this way. Deep down, I knew I'd been abused by my grandfather as a child, but I clung to the idea that everything was fine. We never talked about it, it was a taboo subject. And I knew it myself, but I never remembered it. I had no reason to."

"When I started reacting like this with my daughter, I decided to start this photographic work, to make sure it didn't happen to others. How can I be sure that there are no 'blind spots' in my family? It's a question of trust, really. I didn't want my children to see me as the person who controls everything and trusts no-one. Talking about it means that there are no secrets like that in our family. It's also a way of saying to those who would want to hurt my children: it won't remain a secret, we'll talk about it, so don't even try."

"I spent two years working on the project, with long breaks, which I needed. I wanted to play with the decoupage technique on the photos my grandfather took of me between the ages of three and thirteen. He used to take pictures of me and give them to me, with my name on the back. Sometimes, in fact, I only used the back because there were other family members in the photo. In these photos, there's often a contact between us that may seem harmless, but is no longer so when you know there's been abuse. Especially as I accompany the cut-out photos with captions; you understand that something has happened."

"In the third part of this work, I chose to write a monologue, which resonates as my grandfather confronting me about what he's done. This exchange takes place while we're playing chess - it was my grandfather who taught me to play - and it's at this point that he tells me he's "done nothing wrong". He remains silent. My grandfather died a few years ago and always denied it."

"I went to therapy during the development of this work, but I didn't focus on the abuse during the sessions. It was the artwork itself that helped me. Talking about it, too, with other people who had experienced similar things. I received countless phone calls after that. There were 5 million ways of expressing what had happened to me. I tried several ways before I found the right one."

"Today my first daughter is 5 years old. Of course, she doesn't understand the exhibition, but I don't hide it from her. She's often found herself with me, in the middle of the elements of the exhibition. I simply tell her that my grandfather wasn't a good person, and that he hurt me. What she's found so far is that she can get a lot of colored paper out of my work. I'm glad I'm not hiding that from her."

Cultural recommendations

Also to be read: La Consolation

In this sensitive and poignant story, Flavie Flament breaks the silence and evokes the betrayal of the adults who robbed her of her innocence. It's also the story of a rebirth. A rare book, in which the power of writing is at the service of a struggle. A civic battle, because "to harm a child is to harm the world of tomorrow". Flavie Flament, Le Livre de Poche, 2017

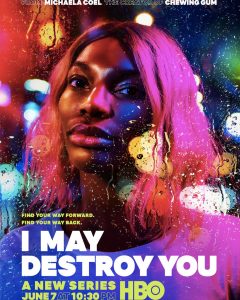

To see: I may destroy you

This fictional series tells the untold story of how a young rape victim tries to remember what happened. From the victims' point of view, the director tackles the themes of sexual violence, post-traumatic stress disorder and dissociative amnesia in this series for which she received an Emmy Award in 2021. "I dedicate this story to all survivors of sexual assault," she said at the ceremony. Michaela Coel, HBO, 2020

Listen to: Mémoire, dis-moi qui je suis?

What does our memory say about our identity? About our relationship with others? To the world? "Memory, tell me who I am" is an immersive 12-episode podcast about memories. Because there isn't just ONE memory, but MANY. Journalist Edwige Coupez meets Marie, Jean-Louis, Pascale... They tell us a personal story or share their professional perspective, shedding light on a particular aspect of memory.